How misinformation spread

It all started with a 2018 commentary paper by Alex de Vries titled Bitcoin’s Growing Energy Problem.

That’s a key detail: it wasn’t a study with new data or replicable methods - it was an opinion piece published in a scientific journal. It was short, only a few pages long and conducted no actual research just kind of collected a set of cherry picked figures and made a set of alarming claims about how much energy bitcoin does, and might use.

The problem is, it was wrong on almost all counts. The reasons Mr de Vries might want to throw shade at bitcoin are up for debate. But the damage he did to the narrative is undeniable.

Commentaries like this are normally subject to a lower level of peer review, because they’re intended to provoke discussion, not to serve as definitive research.

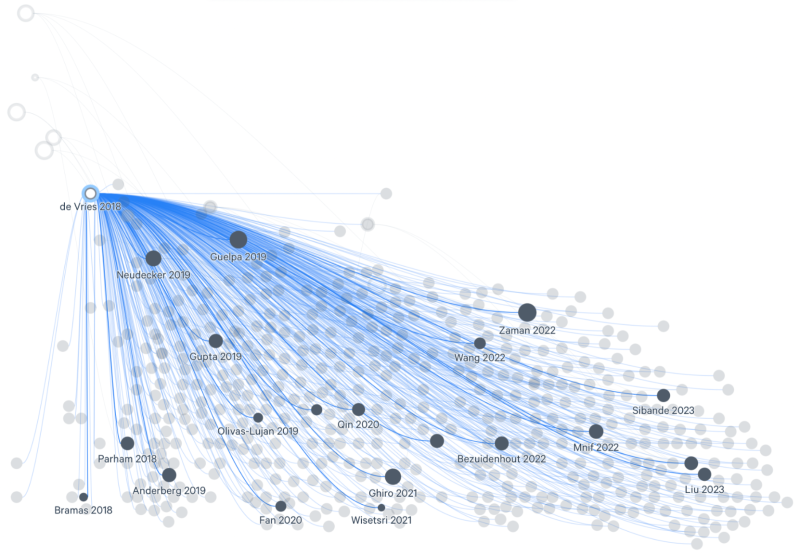

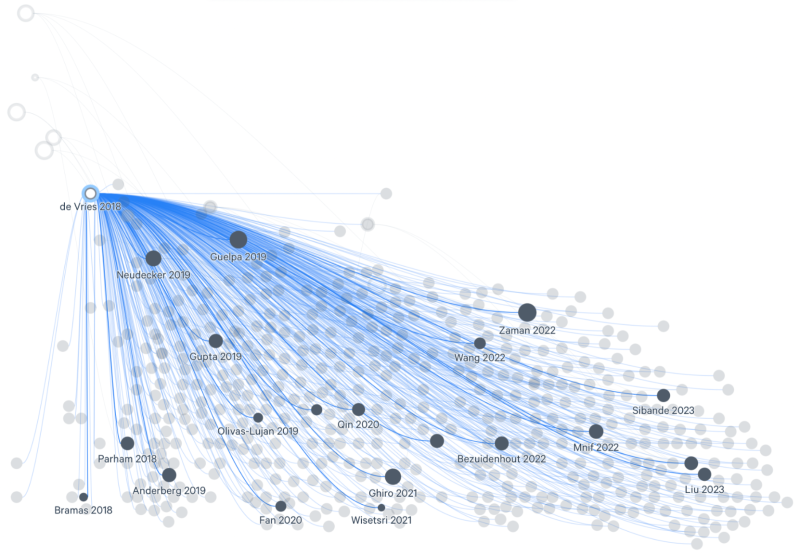

But in this case, the commentary was treated as hard science by journalists and academics alike. It has now been cited over 1,100 times across different databases, often as if it were an empirical study.

Those citations became the seed of a runaway feedback loop:

-

Ten commentary-style papers repeating similar claims (all based on de Vries 2018) have collected nearly 5,000 citations between them.

-

Media coverage amplifies those citations roughly 10 to 1, creating an estimated 50,000 derivative articles.

-

Meanwhile, rigorous, data-driven studies represent only 2 percent of total citations - despite producing reproducible, verifiable findings.

The result is a case study in how weak evidence can gain global traction simply because it’s easy to cite.